Review of An Event, Perhaps: A Biography of Jacques Derrida by Peter Salmon (Verso Books, 2021)

The “Hors livre” [out-book or outside-the-book] of Jacques Derrida’s Dissemination begins with a conclusion: “This (therefore) will not have been a book.” For a newcomer to Derrida, these sorts of shenanigans no doubt appear as self-parody: this is precisely the sort of postmodern chicanery Derrida’s good and earnest critics have warned us about. But if we’re willing to play along, this odd statement raises some interesting questions. If it will not have been a book, does this not leave open the possibility that it is one—at least for the time being? And indeed, the essays in Dissemination—including “Plato’s Pharmacy,” surely a seminal Derridean text—aim to complicate the “being-present” of written works. If it succeeds, one may well conclude that this book about “dissemination” has not (therefore) been a book. This, therefore, will indeed not have been a book—after we have read it. For the first-time reader it remains a book. Only by attempting to affirm it as such—that is, by attempting to read it—can we appreciate the accuracy of Derrida’s opening line. Thus, Derrida’s apparent obfuscation is a perfectly traditional preface. It’s a good joke, especially because he will go on to question the logic of preface writing in general:

Here is what I wrote, then read, and what I am writing that you are going to read. After which you will again be able to take possession of this preface which in sum you have not yet begun to read, even though, once having read it, you will already have anticipated everything that follows and thus you might just as well dispense with reading the rest (Dissemination, 7).

As I’m sure many academics could tell you, a good introduction makes reading the rest of the study superfluous. Derrida wryly observes that in the famous preface to the Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel reaches just the opposite conclusion: “the real issue [i.e., knowledge of truth] is not exhausted by stating it as an aim, but by carrying it out, nor is the result the actual whole, but rather the result together with the process through which it came about.” Hegel’s complaints about the impossibility of prefacing his work nevertheless occur within a preface. Derrida wants to know why this “exterior” activity of prefacing is so troubling to Hegel—is he bothered that the truth isn’t simply present, but must be present-ed temporally, in writing? Derrida asks: “But why is all this explained precisely in prefaces? What is the status of this third term which cannot simply, as a text, be either inside philosophy or outside it, neither in the markings, nor in the marchings, nor in the margins of the book?” (15). These considerations of the “outsides” of things implicate themselves inexorably in the inside and show the importance of writing itself. This therefore will not have been a book, indeed.

Such a brilliant performance will irritate some—and since at least the seventies, has done so with some regularity. But it also shows, with a fair bit of elegance and economy, the most commonly misunderstood element of Derrida’s work. This “deconstruction” of prefaces, or of books, is not meant to destroy or reject them, but to change our relationship to them. Anyone who has ever written an essay can confirm how weird it is to state the argument in advance. Anyone who’s ever taught writing can tell you that students never know precisely how to begin—the thesis statement or introduction is often the last thing one writes. I finished most of this review before I conceived this introduction. A preface or a thesis statement remains an unproven assertion until the essay is complete. Jacques Derrida is not out to destroy the noble preface; he has some questions about prefaces, and some observations about their logic. Derrida’s interventions take the logic of concepts, institutions, texts at their word, and show what happens when it is pushed to its conclusions. He is, in a sense, a very conservative thinker—commenting at length on what can only be called “the great books,” on subjects like speech and writing, love and friendship, death, prayer, and God. The effect of Derrida’s questioning is often decentering, and designedly so. But as with the preface, this decentering can help us see the oddness of familiar things. A recovery of ordinary experience may require extraordinary effort. In his attempt to interrogate such things, Derrida leaves room for a “perhaps” in human affairs. Perhaps, then, we misunderstand Derrida if we see him as an enemy to humanistic inquiry, to philosophy.

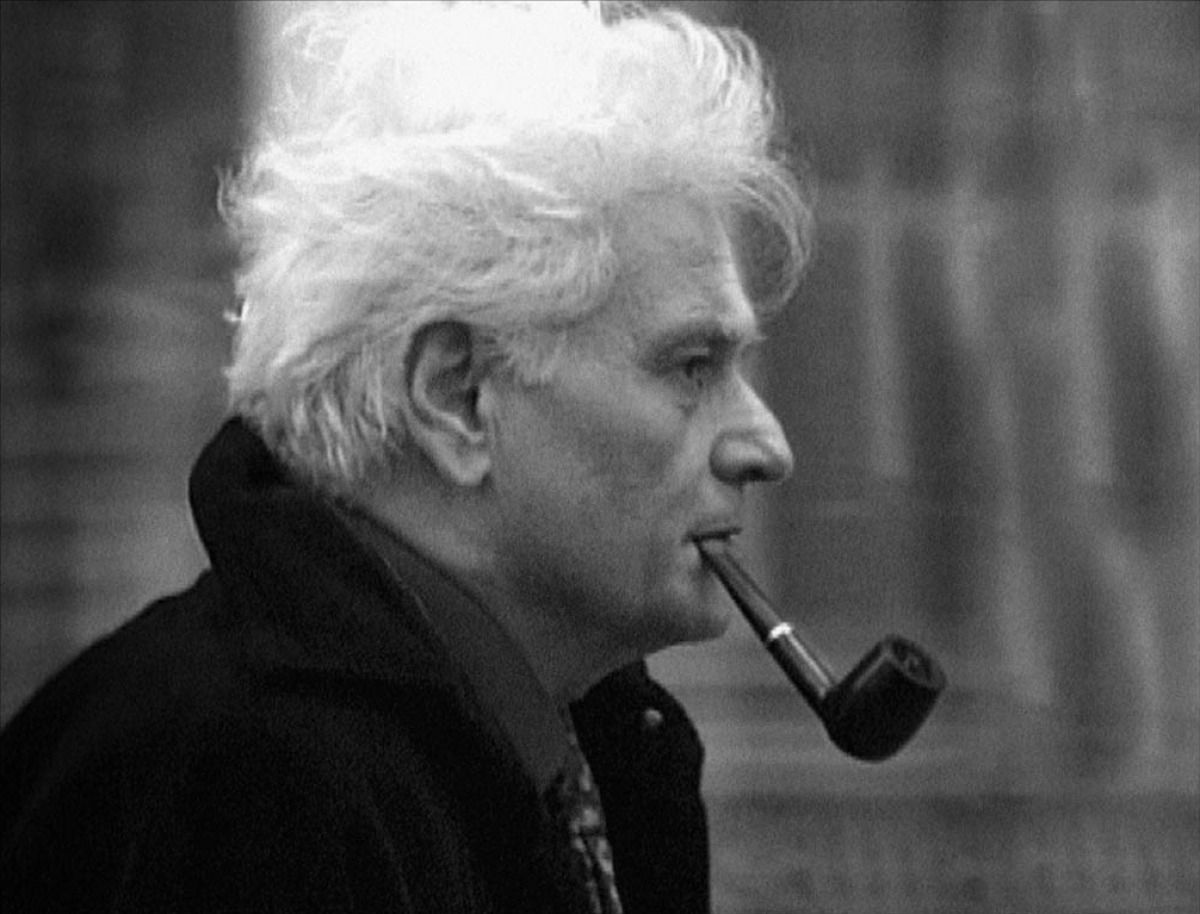

Peter Salmon’s concise new intellectual biography of Derrida, An Event, Perhaps, argues just this. Salmon has a clear thesis about Derrida: his writings are startlingly consistent from the beginning of his life until the end, and he is “one of the great philosophers of this or any age” (4). This is a provocative argument; those fond of Derrida are unlikely to call things “great,” while those fond of “greatness” are unlikely to find it in Derrida. Salmon is furthermore aware of the potential dangers of imposing a strict narrative on the twentieth century’s chief theorist of play: “Derrida’s key concept or fundamental idea is to—and here one immediately searches verbs that are not emphatic—reject (‘reject’), disorder (‘disorder’), complicate (‘complicate’) or, to put it another way, to deconstruct (‘deconstruct’) what we mean by ‘key concepts’ or ‘fundamental ideas’” (3). But An Event, Perhaps illustrates how Derrida’s writings are coherent and respond to important questions, while successfully avoiding both “a kind of panicked rush of obfuscation” and “[t]he temptation to mimic Derrida’s own gnomic, allusive and elusive language” (3-4). If Derrida’s goal is to show the oddness of the ordinary, Salmon’s is something like the inverse: to show how Derrida is just like any other thinker, and thus to situate his intellectual development in private and public life, but also within the history of philosophy.

Salmon, of course, begins with Derrida’s early life, his childhood as “Jackie” Derrida, in Algeria. Jewish and French-speaking in a majority Muslim country, his citizenship and his schooling sometimes in doubt, this early experience of alienation was decisive to a man who would later describe the twentieth century as a “rupture in the structures of belonging.” Derrida eventually arrives at the École normale supérieure where, once again, he stood outside the conflicts between the Talas (Catholics) and the Stals (the Stalinists). Salmon ably shows how, in this tense atmosphere, Derrida took the highly unusual route of writing his dissertation on the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl. Derrida pursued Husserlian phenomenology in part because of its grounding in natural science and its goal of rigor—his concerns much more purely theoretical than the moment seemed to allow.

Salmon’s able reconstruction of the main insights of Husserlian phenomenology set the stage for his description of Derrida’s contribution. Maybe too simply put, Derrida’s insight is that “genesis” in Husserl must abstract from time. Husserl’s science of intentions depends on a moment of apprehension in which time must be represented as standing still; the problem is that time doesn’t stand still, and so the attempt to describe “the things themselves” falls short of its own stated intention. While another normalien, Tran Duc Thao, articulated this problem first, for Derrida, it became an entrée into the entire “metaphysics of presence,” the systematic privileging of presence over absence in the history of Western philosophy. One way of understanding “deconstruction,” then, is that Derrida “is out-phenomenologising Husserl” (99), is showing persistent “phenomenological heft” (111), and “despite his own often abstruse and opaque style, is trying to capture life as it is lived” (119). According to Salmon, this is as true for Derrida’s work on religion and politics in the nineties as it was of his early forays into writing in the sixties.

The central chapters of the book thus proceed thematically and chronologically, weaving Derrida’s work with the events of his life. The chapter on the relation of Derrida’s thought to gender, for instance, highlights his intellectual friendships with women and his tumultuous romantic life. Through the entire biography, Salmon writes with stylish clarity. He is judicious in supplying necessary context—a brief excursus on Levinas, Heidegger, and Judaism; the astonishing tale of the very bad Paul de Man and Derrida’s loyalty to him; a terse summary of Fukuyama’s The End of History to situate Derrida’s deconstruction of Marxism as neoliberalism became ascendant—while also sticking to his thesis that Derrida displays a “meticulous consistency in thought and method” across his varied investigations. There are also enjoyable anecdotes, like Derrida’s first meeting with psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan at the famous “Baltimore Conference” on structuralism—the titular “event,” Derrida’s academic A Star is Born moment. According to Lacan’s biographer, “the pair immediately exchanged terse words on ‘the Cartesian subject.’” According to Derrida, Lacan complained that the new edition of Écrits would be too big, that “the binding might be insufficient, meaning that it could fall to pieces in the reader’s hand.” Lacan “quizzed Derrida about what he knew of binding and glue” (114). Salmon’s restraint in relating these conflicting accounts is admirable, but I know which story I believe.

I also believe Salmon’s main story about Derrida. Salmon’s is not the first biography—there’s the 600+ page Derrida: A Biography by Benoît Peeters, which avoids too much discussion of Derrida’s ideas—nor the first intellectual history to speak about Derrida’s work. And it is certainly not the first introduction to Derrida’s thought. Derrida himself was infected with a case of “archive fever,” writing as many as six memoirs, depending on how you count. But Salmon’s description of Derrida’s thought, his sympathetic presentation of that thought in its various contexts, and many of his evaluations are accurate and insightful.

This is a welcome book at the moment as “French theory” has recently been in the news again. As talking heads attempt to track down the intellectual origins of the identity-inflected turn in contemporary political life, Derrida is not often given the careful attention he deserves. As Salmon duly notes, this line is not new. In 1992, a group of philosophy professors tried to get Derrida cancelled from receiving an honorary doctorate from Cambridge University. Their letter to The Times protesting the degree claimed that Derrida’s work did “not meet accepted standards of clarity and rigor” to be considered philosophy, consisted of “tricks and gimmicks,” and any “coherent assertions” hiding behind his language were “either trivial or false” (quoted in Salmon, 253-4). Far from a nihilistic flâneur, seduced, as another intellectual historian puts it, by “unreason,” Salmon places Derrida firmly on the side of “facts and logic.”

Is Derrida, then, a “great philosopher”? In an age where everyone with a PhD in the subject is referred to as a “philosopher,” maybe we ought to listen to Cambridge dons who complained that Derrida is indeed not like them. To his immense credit, Salmon makes the stakes of the question, and his evidence for a positive answer, absolutely clear. We might therefore wonder whether Derridean deconstruction actually recovers the “real thing” through his readings of classic texts of literature and philosophy. As Salmon persuasively shows, Derrida’s single-minded focus on the promise—and thus the limitations—of reason, in my view, shows an orientation that is precisely the opposite of which he is most frequently accused. But is Derrida in fact guilty of the fault he ascribes to “the tradition”? In Hermeneutics as Politics, Stanley Rosen identifies a “bitter seriousness” behind all Derrida’s play. I don’t know about “bitter,” but I think a certain sobriety characterizes Derrida’s thought. Derrida remains engaged with the Western philosophical tradition because he acknowledges there to be no alternative than to use its language and concepts.

By pushing the logic of certain texts to the limit, Derrida shows that the “dream” of presence cannot be fulfilled. But whose dream is it? Indeed, that Derrida, whose texts evince such exquisite control in their composition, should have doubts about our greatest thinkers’ capacity to do likewise is telling. He is consumed with the possibility of an “undeferred logos” or a “transcendental signified,” or “arche-writing,” and by our ability to communicate this sort of truth. Derrida, in short, might reject the limits imposed on writing by writing, and in this way remains unaware of its possibilities. Derrida’s expectation that all of human experience should be subject to a sort of mastery by analysis seems to fulfill rather than overturn the much-despised Enlightenment project. Derrida, then, is certainly a philosopher according to the very definition of those most keen to say he is not. Is the philosopher fundamentally serious, or playful? Are such inquiries the best way to arrive at originary, pre-scientific experience? Are some of the texts he interrogates actually much more playful on this score than is Derrida? Or is deconstruction instead a rejection of the surface of things which is, after all, also the heart of things? Perhaps.

Matt Dinan is an Associate Professor in the Great Books Program at St. Thomas University in Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada. He invites you to follow him on Twitter.