I tried, trembling, to tell this man all that his writings had done for me…what the first sight of Beatrice had been to Dante: Here begins the New Life.

—C.S. Lewis, The Great Divorce (1945)

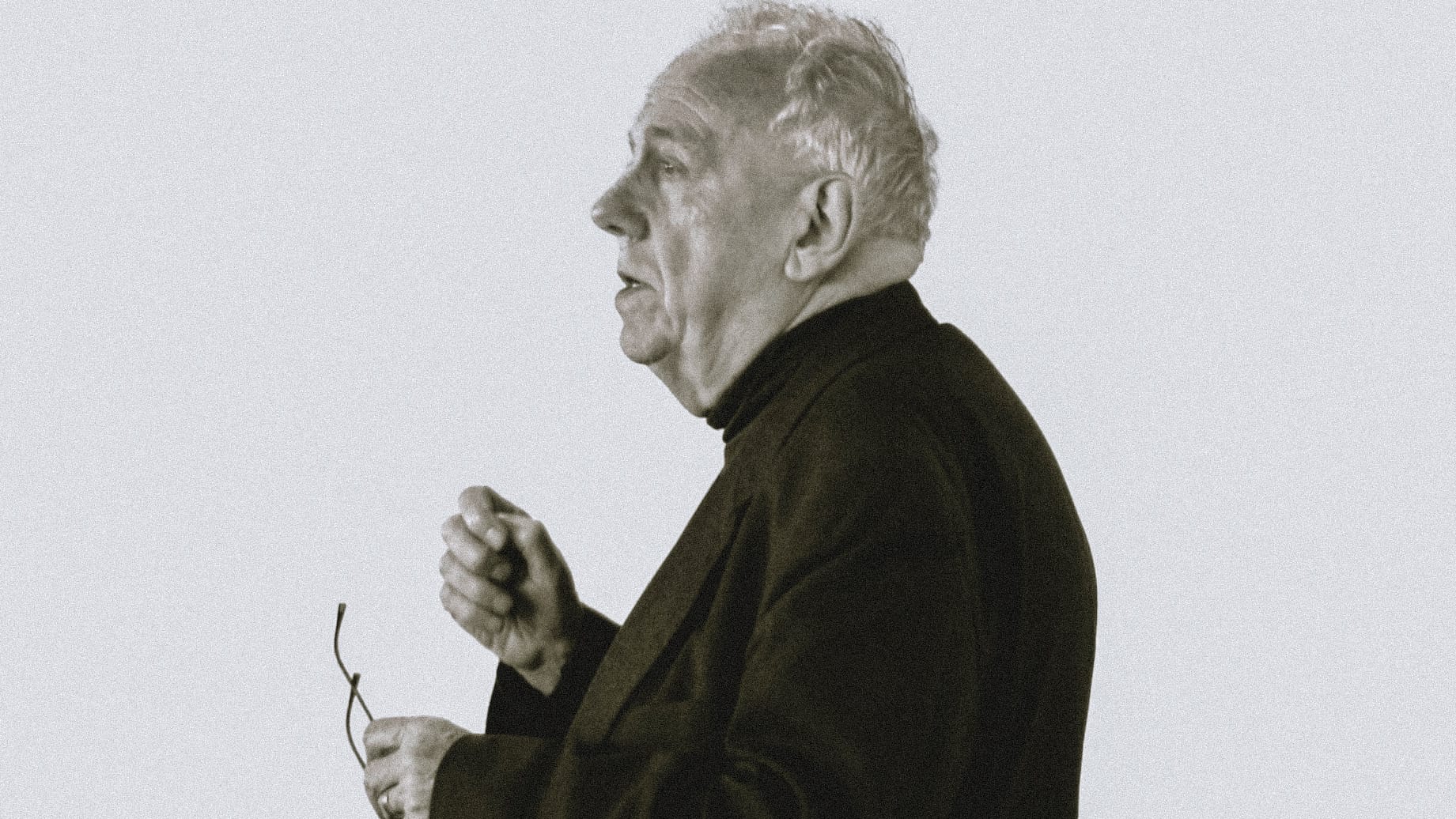

Alasdair Chalmers MacIntyre (1929-2025) died some days ago at age 96. Midway upon the journey of that life, at age 52, he published After Virtue (1981), a book that would define the shape of his career and at least thousands of other intellectual lives—indeed, the entire shape of modern moral philosophy. That book and MacIntyre’s project charged, molded, and transformed the course of my life—among the lives of countless others.

Academics have peculiar relationships to their books. They are more than occasionally our friends, our confidants, our muses—sometimes our foils and foes—but always the blazes that mark the trail of our intellectual journeys. If Eliot’s Prufrock measured out his life in coffee spoons, I have largely measured mine in books.

A few stand above the rest, marking certain inflection points and periods. Plato’s Crito. Homer’s Iliad. Glenn Tinder’s Political Thinking: The Perennial Questions. John Steinbeck’s East of Eden. Eric Voegelin’s Science, Politics, and Gnosticism. Wendell Berry’s Hannah Coulter.

Then there’s After Virtue.

I first encountered MacIntyre as a college sophomore. At the time, I was elbows deep in philosophy, reading Kant, Spinoza, Locke, Hume, and Mill for the series of seminars that would make up my philosophy minor. While I entered (and graduated) my small liberal arts college as a political science major, I turned to philosophy after reading the Crito, in the hopes that it would offer serious moral conversations about human flourishing within the political community.

Even then, I felt something was amiss. Whenever moral topics were broached in class, my classmates—even my professors—were eager to talk about norms, rights, consent, freedom, or emotion. But rarely about virtues, habits, the human being, or his purpose on this earth.

I can’t remember exactly what drew me to Prof. Michael Berheide’s office that afternoon. I gather that it had something to do with my growing disillusionment with my philosophy class. Berheide, the lone theorist in the political science department, listened patiently as I rambled on about the perceived shallowness of “ethics” as a discipline, then interjected: “I think you should read After Virtue.” I walked back to my dorm room, logged onto my computer, and a few minutes later (and $12 poorer), a gently used copy was on its way to my college PO box in Berea, Kentucky.

Borrowing from Walter J. Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz (1959), After Virtue begins with a parable: imagine a world in which the natural sciences are largely extinguished by a world-consuming catastrophe. In the decades and centuries that follow the backlash against scientists, wiser humans try to revive scientific study based on scattered fragments. Perhaps certain terms, formulae, or expressions survive, but not their original meanings. Without the conceptual knowledge, institutional understanding, and scholarly tradition that underpinned their prelapsarian use, they are reconstructed through conjecture to the point of incoherence.

“In the actual world which we inhabit,” MacIntyre suggests, “the language of morality is in the same state of grave disorder as the language of natural science in the imaginary world which I described.” This is the central thesis of After Virtue.

In other words, while we continue to use the expressions and formulae of morality (speaking of duties and obligations and care, even of virtues and character), we “have—very largely if not entirely—lost our comprehension, both theoretical and practical, of morality.” Our moral language is incoherent, confused, and contradictory, because we have lost the entire metaphysical basis stretching from the ancients to the medievals that western language assumed. We are, moreover, largely unaware of this loss.

According to MacIntyre, the moral incoherence of the present age resulted from an Enlightenment project attempting to justify morality without making recourse to teleology, or indeed to any certain sense of what it meant to be a human being. In abandoning Aristotelian teleology—of there being formal and final causes, the virtues, and the human good being bound up in the common good and summum bonum—the Enlightenment left us with little more than emotivism, the idea that ethical claims reveal nothing but the subjective emotional attitudes of the claimant. This diagnosis arrived like a thunderclap in my drizzly gray disillusionment.

Like so many other Christian scholars who came of age in the years after After Virtue, MacIntyre’s arguments deeply formed my intellectual development. Indeed, there are so many of us that it often feels cliché to mention the book’s influence.

Inspired by his critique, I wrote my undergraduate thesis on morals legislation in classical and enlightenment political theory, arguing that enlightenment premises were incapable of sustaining a system of laws aimed at moral improvement, or indeed any goal loftier than restraining the worst products of ambition and competition. It was the work of an enthusiastic and over-confident college senior, as often happens. But the thesis only began to show the debt I owed to MacIntyre. Within that used paperback, as its spine turned pale green with age, I discovered a new world of immense imaginative possibility.

While MacIntyre is often credited, along with Elizabeth Anscombe, for revitalizing virtue ethics in modern political thought, his greater focus lay in arguing for the importance of community in both moral formation and moral reasoning.

Some readers of After Virtue might be surprised to discover a lengthy discussion of Jane Austen among the sections on more well-worn philosophers. Yet for MacIntyre, narrative plays an essential role in the moral life. “Man is a story-telling animal,” he writes, and “I can only answer the question ‘What am I to do?’ if I can answer the prior question ‘Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?’”

Part of the Enlightenment’s confusion lay in its portrait of human beings as blank slates that abstract away from all of their particularities. But this “unencumbered self” (to borrow Michael Sandel’s phrase) does not describe a human being as any human has ever existed. Instead, MacIntyre writes, we each “enter human society with one or more imputed characters—roles into which we have been drafted,” as mothers or children, sisters, brothers, even princes and queens.

In order to live well, we must look to those roles and the practices within our communities that form those characters, and thus our deeper moral character, which is to say virtue. Communities and narratives, like the traditions and morals that flow from them, are not solely the products of consent.

Note that MacIntyre asks, “Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?” rather than the more familiar modern question, “What story would I like to tell about myself?” This is not self-creation, but discovering oneself in an embedded context of people mutually striving to help each other become better people. Narrative and belonging—these were the points that stood out to me as I married, moved to another state, worked through my graduate program, and saw our family grow from two to six.

My wife became pregnant with our first child during the first year of my PhD studies. Suddenly, I found myself drafted into a new, critically important role as a father. As I balanced early mornings rocking a fussy baby and late evenings working on my dissertation, I found myself thinking back to MacIntyre’s enjoinder.

How could I possibly determine how to live a good life, without first knowing what was demanded of me in my roles as husband, father, and member of a church? These roles, moreover, are not lived out individually but within a community and traditions larger than myself.

The last point came home clearly as we named our fourth child, born three weeks ago, after his two grandfathers. As little Timothy Harral grows to adulthood, he will discover what it means to live out his role within a family and community in part by following their model of integrity and moral strength. We are not entirely our own, but belong to a complex fabric of relations and obligations that help narrate our lives.

After Virtue came to be just the first installment in a multi-volume attempt to restore the metaphysical and epistemological grounds of moral philosophy, which unfolded across tomes such as Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (1988), Three Rival Versions of Moral Inquiry (1990), and Dependent Rational Animals (1999), as well as God, Philosophy, and Universities (2009), and Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity (2022).

Over these decades, MacIntyre gradually worked out what it meant to reason from within a tradition and community, eventually departing from Aristotelianism strictly speaking for a philosophical Thomism rooted in biology. In Dependent Rational Animals (which I read on my own in graduate school), MacIntyre rejects the rational atomistic modern self by highlighting the dependence and vulnerability that permeate all human life, reiterating the fundamental importance of communal affection and support.

Therein, however, lay one of the great paradoxes of the philosopher’s life. He was, even by the standards of academe, something of a nomad.

After completing a Master of Arts degree—he never held, and was one of last lucky few academics who never needed to hold, a Ph.D.—MacIntyre taught at several British institutions before moving to the United States, thereafter rarely spending more than a few years in the same place, until he eventually settled at the University of Notre Dame. He taught at roughly a dozen different institutions, married three times, and experienced both religious apostasy as a Protestant and conversion as a Catholic.

While he was much beloved by many students, readers, and colleagues, others found him more difficult to stomach. His acerbic wit and exacting standards alienated some, his idiosyncratic readings of the history of political thought alienated others. His Catholicism and Thomism were reason for many in the academic mainstream to marginalize him, treating his ideas at best with a sort of bemused half-attention, as a quaint curio in a field that remained dominated by analytic rationalism.

MacIntyre’s ideological wanderings were no less striking, from analytic philosopher to card-carrying Communist Party member to Aristotelian to Thomist, with more than a few stops along the way.

Long after abandoning the Communist Party, MacIntyre retained Marxist critique as he remained sharply critical of capitalism, such as remarking in 1996 that he “would still like to see every rich person hanged from the nearest lamppost.” Then, in 2004, he wrote a short essay suggesting that the “only vote worth casting” in the election between George W. Bush and John Kerry was to not vote at all. After all, MacIntyre was a thinker who could argue that patriotism was a virtue, all the while suggesting that being asked to die for the modern state is “like being asked to die for the telephone company.”

As the rare contemporary academic like René Girard whose influence went far beyond any initial expectations, MacIntyre was not always receptive to his large following. He might not even have been at home among those most sympathetic to his ideas—a group of largely religious and “post-liberal” thinkers. He disparaged (and perhaps refused to read) Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option (2017), which the author drew from the conclusion of After Virtue where MacIntyre suggests that rather than “waiting for a Godot,” we are (or should be) waiting for “another—doubtless very different—St. Benedict.”

What does it mean then that the author who argued for the essential role of community and tradition in our moral formation and reasoning is hard to place within a community?

MacIntyre’s wandering was not permanent, however. He settled on Lynn Joy (his third wife, whom he married in 1977), Catholicism (in the 1980s), and the University of Notre Dame (1989–2025). Perhaps MacIntyre’s communal focus was as much cri de couer as polemic, and he finally succeeded in answering for himself the question he asked us each to consider: of what story do we find ourselves a part?

In answering that question, we may find ourselves a part of many stories. MacIntyre found himself unknowingly a part of my story. The closest we came to meeting was when he left a voicemail politely declining my friend’s invitation to speak to our After Virtue reading group at the University of North Carolina. Even after his death, he remains central to the story and practices of my studies, my teaching, my family, and my faith.

Here at Elon University, for example, I teach “Introduction to Political Theory” some three or four times a year. The students who enroll are, for the most part, neither familiar with nor interested in political theory or philosophy. While I do not assign MacIntyre’s work in the class, his spirit shapes the entire frame of the course, which surveys various approaches to justice and the good life from Sophocles’ Antigone to the present.

Plato’s Gorgias, which we read in the opening unit, poses a single question that looms over the rest of the semester: which life will you choose? Socrates, or Callicles? Philosophy and contemplation, or domination and desire? Even the greatest hits of Enlightenment political theory are incapable of moving us entirely away from that question, and offer unsatisfactory answers of their own. If the current moral discourse is untenable, then, will you have Aristotle or Nietzsche? Each of you must determine what to do with, as Mary Oliver pens, “your one wild and precious life.”

Alasdair MacIntyre answered, if imperfectly, this question: to pursue life in a moral community; to discover what roles you were drafted to play in its common story; to care about practices and how they shape your soul. And, in MacIntyre’s case, to inspire generations of scholars and students to ask and answer those same questions.

For endless numbers of people like me, the world after After Virtue was never quite the same—as evidenced by the dozens of in memoriam essays and heartfelt tributes written by souls inspired and influenced by their teacher. But while many knew him personally and stood in loftier positions than I, my case is like most readers who feel the deep debt to his awakening us to the seriousness of how to practice the moral life.

MacIntyre’s voice carried beyond Notre Dame and Duke and other elite circles. After Virtue has been translated into over a dozen languages and has sold over 100,000 copies—more than enough for a used copy to come into the hands of a nineteen-year-old student in rural Kentucky to restore his faith that political theory could be turned to questions of virtue and flourishing.

This fruit is, in my view, the most beautiful thing about MacIntyre’s legacy.

In a brief prologue written for the third edition, entitled “After Virtue after a Quarter of a Century” (2007), he writes, “those elites never have the last word.” Rather, "when recurrently the tradition of the virtues is regenerated, it is always in everyday life” and “always through the engagement by plain persons in a variety of practices,” like “making and sustaining families and households, schools, clinics, and local forms of political community.” For, MacIntyre states, “it was they who were the intended and, pleasingly often, the actual readers of After Virtue.”

While reading After Virtue helped lead me to a career in academia, more important is that MacIntyre reiterated for me and for others the immense value and moral worth of the mundane: of faithfulness in serving our families, churches, and cities. There is in the serving of soup or rocking of a newborn child the opportunity to build a good and beautiful life. What a precious role to play indeed.

Matthew Young is an Assistant Professor of Political Theory at Elon University. A contributor to Voegelin View, he is writing a book on toleration, hope, and the apocalypse. His work can be found on his website and on X.