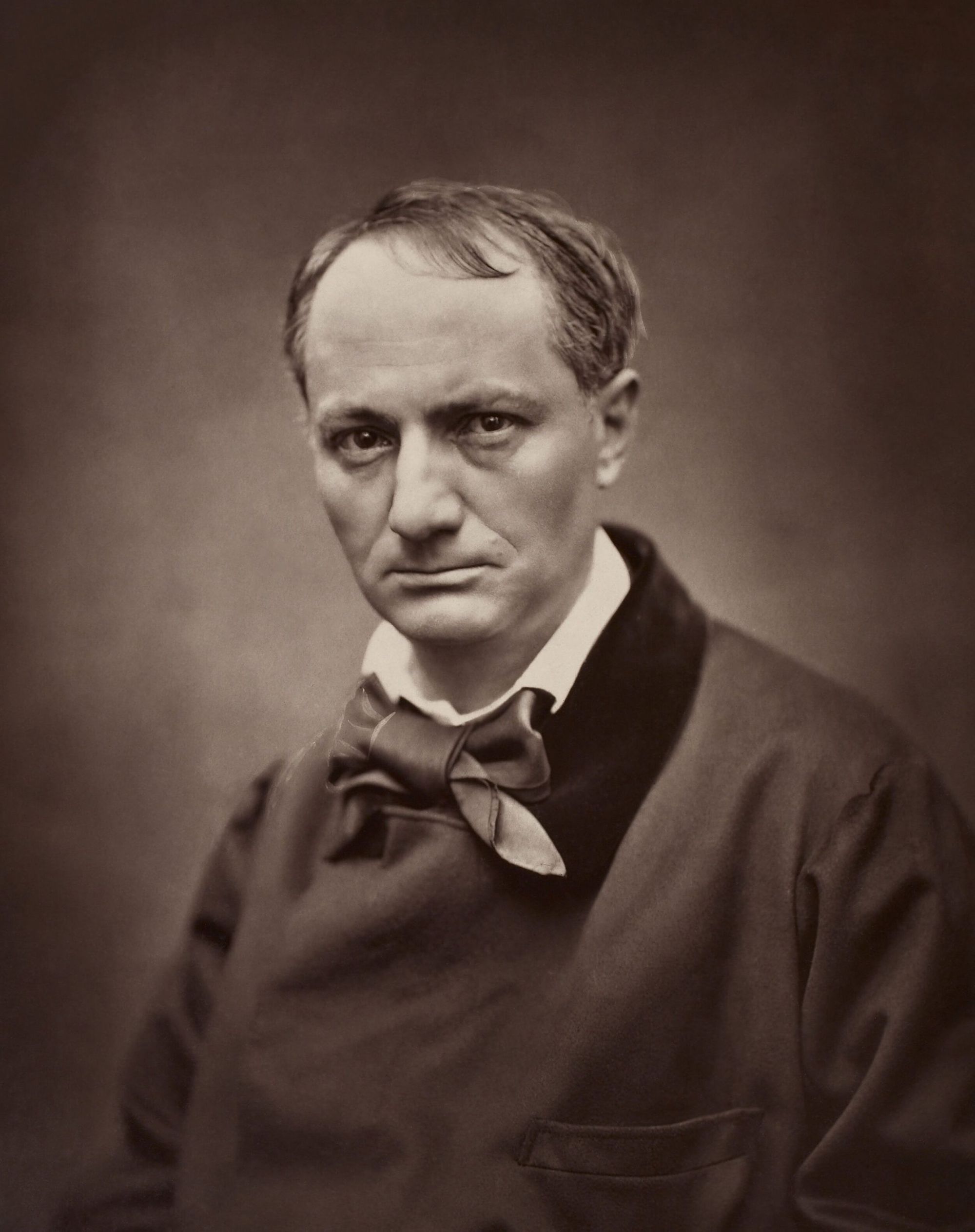

For gauging the mood of an era, art generally precedes theory. The theory of the twentieth century oftentimes systematized—gave causes for—the mood described by the nineteenth century’s artists. For our part, we are living through a continuation, or better an intensification, of the nineteenth century’s spiritual problems. In my last essay, I sketched a critique of liberal modernity currently developing on the right and tried to explain how various causes coalesce into a pervasive, unarticulated malaise or dissatisfaction. But sometimes it’s analytically useful to break down this malaise and to magnify its strands. There are many things that feed our present discontentment, and we benefit from articulating its components–even if we never experience them in isolation. I want to isolate one strand in particular—spleen, described by Charles Baudelaire a century and a half ago—for this reason.

In Les Fleurs du Mal, Baudelaire contrasts spleen and the ideal. The ideal—something like beauty—gives life its meaning and can revivify a dead world. Spleen, on the other hand, is an anchor that drags us on our ascent to the ideal. And it is clear Baudelaire thinks spleen predominates. The word appears throughout the collection, but Baudelaire entitles a quartet of poems—distinguished only by their numerals—“Spleen.” We can better isolate this strand of modern malaise by glancing at these poems.

It is clear that, for Baudelaire, spleen is a more active force than his other main mood, ennui, which is something like strong, persistent apathy. Spleen is more sinister, leading to a depressed self-alienation. Where once we were “living material” (matière vivante), our bodies and our spirit have now separated. A body is nothing but “granite,” a “skeleton,” a “corpse” that we observe from without. It is surrounded but not unified with the spirit, which Baudelaire calls a “vague terror” (vague épouvante), “unknown to an indifferent world” (ignoré du monde insoucieux). More than loneliness, it is a terror that we will live invisible to all others and that, when the time comes, we’ll have nobody to call on—the terror of a meaningless life.

Of course, that a person is lonely need not drive them into despair. They might, of course, be sustained by the hope of escaping their isolation, of forging some lasting, fulfilling connection that gives meaning to their past lonesomeness as some necessary part of their life’s narrative. Spleen, however, denies them this hope. Playing with the image of hope “taking flight,” Baudelaire calls hope a “bat,” that, captured, “flaps against the walls and bangs its head on the ceiling” (battant les murs . . . et se cognant la tête á des plafonds). Hope thus cannot alleviate this terror. Spleen ensnares hope, which, starving, eventually dies.

Nor does Baudelaire ultimately think that distractions will solve the problem. The quartet’s third piece describes, of all people, a prince, whose spleen is unassuaged even by his limitless royal luxuries. He scoffs at his jester and his courtiers, his constant royal entertainment; his royal bed “transforms into a tomb” (se transforme en tombeau). He cannot even feel pride in his rule, which might as well be that of an impotent old man over a “rainy nation” (pays pluvieux). If this is the fate of a prince, then what can the faceless urban multitude do? As Walter Benjamin reminds us, they lurk just beneath the surface of Baudelaire’s text. To what can they turn to help themselves? Powerless, poor, and isolated, they must experience, we think, something incomparably worse.

These lines should immediately call to mind what we loosely categorize today as “deaths of despair” that are driving the decline in American life expectancy. Mostly suicides among young, single men, these deaths arise out of a hopeless isolation exacerbated by a trio of distractions: opioids, pornography, and screen time. They belie the notion that rising standards of living correspond to rising levels of satisfaction. Given the commodities at our disposal, we are today afforded distractions more akin those of Baudelaire’s prince than of the urban rabble. That we have not assuaged our spleen shows that this is a crisis of something far more fundamental and far more difficult to correct.