On Marshall McLuhan’s Catholic Globe

Review of Digital Communion: Marshall McLuhan’s Spiritual Vision for a Virtual Age, by Nick Ripatrazone (Fortress Press: 2022).

Conflicting Visions of the Internet

Current hysteria over fake things on the Internet has stoked a lively debate on what the Internet should be, but too little about what it presently is and how it came to be. Routine complaints levied against AI-generated imagery and various instances of “fake news” center around their capacity to steer observers away from some objective reality. This alleged transgression, in turn, has led to the wholesale condemnation of communities creating such content and the software tools to make it.[1]

Remarkably, anything that is a digital projection of the imagination is now on the chopping block, yet that greatest facility of the human mind is the origin of creativity and culture. Whereas television was invented as a one-way medium, the internet is interactive, and remains supported by software designed to tap into the mind and transmit what is found there to others. The imagination is also the gateway to a greater spirituality—the ability to think beyond the immediate confines of one’s physical environment. While many tend to think of fake news as the product of devious political operatives attempting to manipulate a gullible public, an awareness of how culture comes to be shows misinformation to be overly maligned.

But this point of departure involves a fundamental debate over what it means to be online. Since the dot-com era, there has been a conflict brewing between two competing visions of the Internet: a rationalist view versus a liturgical view over what the Internet really is.

On the one hand, we have the rationalist vision of an Internet that serves as the world’s database of factual knowledge, as facilitated via the digital logic of the underlying hardware. This version is the vaunted “Information Superhighway” of the 1990s, Al Gore’s vision of global information flow that businesses and governments advocated for in their relentless promotion of the World Wide Web as a new forum for commerce and office productivity. One television advertisement released at the turn of the millennium went:

Something magical is happening on the planet. It’s growing smaller. Every day the global web of computers weaves us more tightly together. Join Us. Wander through a distant library. Turn your corner store into a mini-multinational. Curious? IBM can get you there. Just plug in, and the world is yours.[2]

Notably, nearly every clause or sentence is spoken by someone in a different language, though with English subtitles: a diversity without substance that’s emblematic of this soulless vision.

The Information Superhighway, while maybe an attractive idea to the humorless suits at IBM, did not resonate with the public. Yet it was also never abandoned by its strongest adherents. Today, we find this vision upheld by rationalist communities on the web, who invoke it as a basis for their critiques levied against the fictions found online. And those critiques, of course, are routinely deployed as a crutch in partisan arguments. It’s a sophist’s game, but one that directly connects to the nature of online communication.

Decades ago, one man attempted to understand why this intersection of engineering and business was spawning new information networks. That droll patriarch of mass communication, Marshall McLuhan, aptly observed that the world “of mechanized routines, abstract finance and engineering is the consolidated dream born of a wish.” But “by studying the dream in our folklore, we can, perhaps, find the clue to understanding and guiding our world in more reasonable courses.”[3] In other words, to be stuck in a static rationalist account of modern media would leave one with only a partial understanding of what an information network actually is. Emphasis must then be placed on the realm of the imagination, where wishes, dreams, and folklore all bolster our collective experience.

The Internet, first and foremost, is a social technology, a symbolic liturgy with its own tribal cues and icons, signs and wonders. The facts, if they exist at all, do not matter. Rather, the Internet’s communicative capacity lets people transmit fragments of their imaginations to others—a feature users find most tantalizing because it amplifies culture in new ways. The medium is the message. Always has been.

Thus, on the other hand, we have the the liturgical vision, one of a more freewheeling Internet, as articulated by McLuhan, that acts as a lively countercultural alternative to the bland database of facts. In this Global Village, the synthesis and exchange of information tightens the interconnections of a network’s geographically-dispersed users. As early as the 1980s, many adherents converted to this perspective: from programmers, science-fiction writers, and computer hackers, to digital artists, gaming enthusiasts, and many others, all desired to share their imaginations with a global audience running rampant across the digital substrate envisioned by McLuhan.

Today’s Internet looks far more like Whole Earth Catalog editor Stewart Brand’s WELL, an early online community inspired by McLuhan’s writing, than it does Gore’s Information Superhighway.[4] The “Global Village” model brings the world more tightly together, not in a crass commercial sense, rather as a communion in a spiritual sense. McLuhan’s ideas were an amalgam of current trends in engineering, and—almost paradoxically for a figure intimately tied to the 1960s counterculture—a deeply rooted and traditional Catholic spirituality. On this basis, Wired, the flagship magazine of the dotcom era, dubbed him the “Patron Saint of the Internet” in its 1993 inaugural issue.

McLuhan’s Faith

Which brings us to Digital Communion (2022), Nick Ripatrazone’s svelte and punchy new volume on McLuhan’s little remarked upon, yet far-reaching spiritual vision for our virtual age. Ripatrazone, with a journalist’s eye, connects the most salient aspects of McLuhan’s life and work with prominent twentieth-century figures and trends in Catholicism to tell this fascinating story. Its basic thesis, that the Catholic Church had a hand in the creation of the modern Internet’s culture, feels surprising, but perhaps shouldn’t be. For, Ripatrazone argues, a proper reconsideration of McLuhan’s theories in light of his Christian faith should change our popular understanding of the Internet in a profound, and perhaps hopeful, way.

As a Catholic—and a convert helped along by the writings of G. K. Chesterton, no less—McLuhan was a participant in the ultimate media system, one that sacramentally connects the pious on earth to the faithful departed, angels in Heaven, and the Most Holy Trinity. Such a spirituality is a cacophony of strange transmissions—ones bearing little resemblance to the fads of strictly rational thought and factual knowledge that became fashionable following the Enlightenment and the subsequent development of economic liberalism. Rather, it took an innovative thinker like McLuhan to recognize that the rational foundation of contemporary technology could be leveraged in fundamentally irrational ways to advance humanity. In his own words: “My increasing awareness has been of the ease with which Catholics can penetrate and dominate secular concerns—thanks to an emotional and spiritual economy denied to the confused secular mind.”[5] Indeed, this premise was to be the prevailing strategy of McLuhan’s research on the media.

Ripatrazone emphasizes the low-key nature of the Catholic influence within McLuhan’s writings and lectures. Rarely explicit yet nearly always implicit, it consisted in the weighty goal of making information networks centers of human creativity—a distinctly human capacity that stems from people being made in God’s image and likeness. Importantly, McLuhan emphasized a social aspect to creativity by linking it to the Global Village, a term for human society as forged by mass media, which became McLuhan’s signature idea when first introduced in the late 1950s.

In context, this concept was a clear reaction against a stark period of social alienation and aggressive political nationalism spanning from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century and culminating in two devastating world wars. The Global Village is also consonant with Pope Leo XIII’s call to family, community, and participation in Rerum Novarum—a document that attempted to head off the horror that would eventually come to pass decades after it was published. What had been missing until the mid-twentieth century, according to McLuhan, was the unifying force of global information networks. “The electric movement of information abolishes the walls and boundaries between subject matters as much as between night and day and nationalities,” McLuhan writes, and “the tribalism will consist of one tribe in one global village—to wit, the human family.”[6]

However, this was not a utopian project. According to Ripatrazone, the Global Village “could be disastrous or wonderful—or both.”[7] McLuhan and graphic designer Quentin Fiore ended The Medium is the Massage—their bombastic manifesto promoting the Global Village in the context of the 1960s counterculture—with the words of philosopher and mathematician Alfred North Whitehead: “It is the business of the future to be dangerous.”[8] Never having been a retreat from challenge, the Catholic faith is indeed predicated on the necessity of difficult social engagements, in imitation of Christ’s interactions in the Gospels. Some friction is necessary, but that friction should not reduce to disembodied argumentation—one needs to feel it. To McLuhan, an effective electronic medium was a new appendage of humanity’s central nervous system.

So how exactly does one get to this new virtual age? It takes more than just the development of the underlying technology; there is also a need to engineer the medium’s cultural capacity.

McLuhan the Irish Meme

At its essence, the Global Village consists of an elaborate mosaic of ideas in the mode of what Julia Kristeva calls “intertextuality,” that any piece of media is in potential relation with every other.[9] And with electrical media, every person is likewise in potential dialogue with every other.

In developing this concept, Ripatrazone draws a connection to James Joyce: this fellow (albeit lapsed) Catholic’s work served as a prototype for McLuhan. Enough so that the pages of the Washington Post once joked that “McLuhan, at times, does talk like a character that Joyce might have created.”[10]

The often maddening and fragmentary nature of McLuhan’s prose mirrors that of Joyce: for both linear connections between points of information inadequately express human experience. That is why, crucially, McLuhan made the leap to visual media: he celebrated the emergence of television as North America’s premier communications medium at the previous midcentury, and he anticipated the more participatory visual mediums later made possible by today’s multimedia computer technology.

While Joyce could not remix visual representations of replicated information in a work like Ulysses, now anyone can do this using a meme through the Internet. That memes have become an entirely new form of communication, with their own pedigree, rituals, and standards, is a testament to the validity of this synthesis of thought between Joyce and McLuhan. In his later career, McLuhan operated as his own meme, replicating his trademark phrases in television appearances, and famously portraying himself as a character in the Woody Allen comedy, Annie Hall (1977).[11] He naturally relished this new way of living. “In this electric age we see ourselves being translated more and more into the form of information,” he writes, “moving toward the technological extension of consciousness.”[12]

For Ripatrazone, Joyce is not the only Irishman who foreshadows McLuhan. Remarkably, he also identifies William Butler Yeats, a mystic of a different sort, as a cornerstone to McLuhan’s thinking on information networks: “Like Joyce, Yeats was able to channel ‘myth, in manipulating a continuous parallel between contemporaneity and antiquity.’”[13] This line about myth as a bridge between antiquity and modernity comes originally from T.S. Eliot, who says that thanks to men like Joyce and Yeats, “instead of narrative method, we may now use the mythical method.”[14] This method was fresh in the twentieth century, being simultaneously pursued by writers like Joyce, poets like Yeats, and even scholars like Claude Lévi-Strauss. When combined with information networks, its power would be vast in the century to follow. Something Marshall McLuhan well understood.

The use of myth as a filter for the complexity of human experience stands in stark contrast to the rationalist desire to stick solely to the facts, since any lapse into the imagination would allegedly ensnare the mind in ignorance. Modernism as an artistic movement was a reaction against this dim view of humanity. But it took digital technology to resurrect myth cycles at a global level and elevate them to new heights. On the Internet, we see this dynamic in fandoms, gaming universes, virtual communities (especially political ones), and Silicon Valley’s present fascination with generative AI.

A Long Tradition

Consonant with all these themes, the Holy Mother Church’s interest in the media began long before McLuhan arrived on the scene. There is no fundamental incompatibility between information networks and the sacred if said networks allow their users to experience transcendence and enter into meaningful communion, or spiritual closeness, with others. Possessing some aspect of these features, the new mediums of radio, film and television were ripe for evangelization in the early twentieth century. (For good reason modern radio’s inventor, Guglielmo Marconi, personally set up the first papal broadcast in 1931.)

In particular, following a calling received through prayer on the eve that divided the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Blessed James Alberione recognized the vast potential of the mass media for Catholic education and evangelization. He established the Pauline Family, a set of religious congregations meant to address the spiritual needs of a world reconfiguring through technological acceleration by embracing new innovations in the media. The pervasive presence of the Daughters of Saint Paul, one of the Pauline congregations, on various social media platforms today demonstrates the durability of Alberione’s movement.

Further, Ripatrazone uses the example of Pope Pius XII’s encyclical, Miranda Prorsus, to highlight the Church’s satisfaction with a media that “can assuredly provide opportunities for men to meet and unite in common effort.”[15] McLuhan, when he converted to Catholicism in 1937, entered a church already gearing up to mint television personalities like the Venerable Fulton Sheen and Mother Angelica.

Flashing forward to the early 1990s, the openly Christian executive editor of Wired, Kevin Kelly, was setting an agenda for the Internet era that would encompass creation and communion—elements that would prove irresistible to counterculture enthusiasts in Silicon Valley and conservative Catholics alike.[16] Ripatrazone surfaces a remarkable article published by Christianity Today that recounts an encounter Kelly had with virtual reality pioneer Jaron Lanier, one that led him to a profound spiritual revelation. Kelly came to believe that the ability for programmers to create wholly new digital environments was most importantly a luminous “vision of the unbounded God binding himself to his creation.”[17] This new act of creation was enabled by the capaciousness of computer programs and the unbounded reach of information networks. Such capabilities are familiar enough to the public, but are not typically associated with Christian spirituality.

Wired’s editorial board would converge on Kelly’s agenda of not only seeking to understand a rapidly changing globe, but also to fix it in constructive ways. But they needed to put some intellectual heft behind that agenda to get the techies, who tended to fixate on technical minutia rather than technology’s broader social context, onboard. In this regard, McLuhan’s ideas were seen to be explanatory and instructional in just the way Silicon Valley required.

In the realm of ideas of the early 1990s, when a more disconnected critical theory that stopped at its own critique was prevalent, it was a bold turn. Backing the “canonization” of McLuhan, the first issue of Wired provided a conversation between the WELL’s Brand and feminist social critic Camille Paglia on the primacy of the media, with Paglia recalling as a graduate student: “We all thought, ‘This is one of the great prophets of our time.’” And yet asking:

What's happened to [Mcluhan]? Why are these people reading Lacan or Foucault who have no awareness at all of mass media? Why would anyone go on about the school of Saussure. In none of that French crap is there any reference to media. Our culture is a pop culture. Americans are the ones who have to be interpreting the pop culture reality. … What we have is total domination by the pop culture matrix, by the mass media matrix. That's the future of the world.[18]

And thus, McLuhan’s legacy was sealed as the prophet of that world.

To Oblivion and Beyond

But that legacy has not escaped untarnished. It’s important to look critically at McLuhan’s work in the context of the infrastructure it went on to influence.

Ripatrazone is fundamentally upbeat (as am I) about the contemporary Internet existing as an incarnation of the Global Village. But significant problems can be found in the current implementation, which is reliant on surveillance and leaves the impulses of wayward souls entirely unchecked. The root of this problem is the centralization of the infrastructure, which has led to tight social control by the government in China, and monetized behavioral monitoring by corporations in the United States. There are other paths to connecting the globe that do not end in tyranny, such as a constellation of decentralized sites run by autonomous communities,[19] but these have fallen out of favor as programmers have chased money and power by concentrating millions into large platforms that compel their users to be chronically online.

“Today we can recognize,” as Pope Francis laments the state of social media, “that we fed ourselves on dreams of splendor and grandeur, and ended up consuming distraction, insularity and solitude.” For, having “gorged ourselves on networking,” we “lost the taste of fraternity,” and having “looked for quick and safe results,” we only found “ourselves overwhelmed by impatience and anxiety.” The “prisoners of a virtual reality, we lost the taste and flavor of the truly real.”[20]

As one example, the most formidable virtual prison is, of course, the colossal ecosystem for online pornography, which millions of people are gorging themselves on and being consumed by at any given moment. McLuhan was intrigued by the visceral effects of communications mediums, which would only become more intense through technological progress. He revised his trademark phrase, “The Medium is the Message,” when titling The Medium is the Massage,[21] to emphasize that a medium was more than just a conduit for information, but a source of personal formation: “It takes hold of them. It rubs them off, it massages them and bumps them around, chiropractically, as it were, and the general roughing up that any new society gets from a medium, especially a new medium, is what is intended in that title.”[22]

That users can actually feel something through the Internet is not necessarily a bad thing – and McLuhan’s interest in the associated phenomenon hints that he was not in favor of a complete abandonment of the physical body. The goodness of the embodied experience of computer networking is especially true in online experiences that foster fraternity. But which sort of fraternity, and by what mediating source? The illusion sold by an algorithm and a corporation, or something that results in a substantial common good in place and time? There is a danger when this particular feature of a medium is exploited to its logical conclusion for commercial purposes.

In film, the dystopia which this logical conclusion inhabits was famously examined by another one of those McLuhan memes, David Cronenberg’s body-horror flick, Videodrome (1983). Having heard McLuhan’s lectures while a student at the University of Toronto, Cronenberg had his film serve as both an homage to and critique of his teacher’s media theory: “I refuse to appear on television,” as McLuhan’s stand-in, Professor Brian O’Blivion, explains, “except on television.” Cronenberg makes the point that when viewers are given access to a feed of mindless yet shocking content (such as tortured naked bodies) through a visual medium (such as on television), they will not turn away. While this business plan locks-in customers for a content provider, those customers eventually self-destruct because they are separated from the truly real.

Ripatrazone explains that “Videodrome is what happens when a self-described existentialist-atheist channels McLuhan—but makes McLuhan’s Catholic-infused media analysis more secular and raw.”[23] Anecdotally, folks in Silicon Valley have mentioned to me how often programmers have learned about a new business idea for their social media company by watching Videodrome, which, to be fair to Cronenberg, is quite likely the exact opposite of any intended lesson. This obliviousness is perhaps perilous for those who naively find their way to McLuhan through Cronenberg.

A more nuanced dilemma for the modern media is the reconciliation of physical and virtual spaces. Ripatrazone is particularly concerned with this problem in his attempt to provide a roadmap for applying McLuhan’s ideas to today’s Internet. His somewhat radical plan calls for virtualizing spaces left untouched by high-tech innovation, including the invention of digitized sacraments as a response to the Eucharistic separation congregations faced during the coronavirus pandemic. What McLuhan himself would make of this idea is worth some speculation.

We know that he was a devotee of the Traditional Latin Mass, and opposed the reforms made to the Roman Rite during the Second Vatican Council. Even the mere introduction of the microphone to mass was an unwinding of the celebration’s spiritual reach to McLuhan, who complained that its effect, besides rendering the possibility for meditation and a church’s acoustics impossible and meaningless, was “to turn the priest around to face the congregation, so that now he ‘puts on’ the congregation rather than putting on God.”[24]

Thus, from McLuhan’s perspective, there are some physical places that are sacrosanct because they have already achieved divine perfection. Consequently we are left with a difficult question of how one who is spiritually-inclined properly situates a virtual space in their life?

It is presumptuous to wish for digital sacraments, as Ripatrazone does. Beyond virtually impossible, it’s categorically so. All seven sacraments require physical presence and embodied gestures, be they an “I” invoking the Trinity to the hand or use of hands by the priest. None work without their proper conditions, such as the Eucharist sans unleavened bread and grape wine. But offered by digital screens? Food for thought, I suppose, but malnourished. Given that our Lord refused to turn stones into bread, perhaps it would be unwise to try it with memes.

Nonetheless, the overall promise of McLuhan’s spiritual vision outweighs the problems, because within it, he recognized a perfection in Christ as a medium: “In Jesus Christ, there is no distance or separation between the medium and the message: it is the one case where we can say that the medium and the message are fully one and the same.”[25] The more Christ-like the medium, the more perfect it will be, and the better we will be by the use of it.

An Internet of Souls

The Internet is distinctly different from print, radio, and television because it is interactive, allowing projections of the human imagination to become its input. That we have been made in the image and likeness of God means our handiwork, like His, is, at least in principle, good. The Internet has always been a project of our subcreation, and therein lies the potential roots for its salvific use. We are a fallen species, but in light of Christ’s redemption, a media theorist like Marshall McLuhan can help us think about how to build and wield our technology well.

There is a certain inevitability of turnover in communications mediums through technological progress. Multiple mediums are at play when it comes to the Internet: text, images, video, and so on. And new mediums like AI are also finding a home there. The Internet, in some sense, is a meta-medium, and thus will likely stand the test of time even as more specific mediums come and go. We no longer use clay pots to remix and transmit scenes from stories as in antiquity, but pots are still being made and used. In turn, the Internet may be superior to older mediums used in the physical world because it allows us to project more of imagination to others. But toward what end?

Here the liturgical vision of digital technology gives us some hints. Over time, humanity has been moving to become discarnate through new mediums in a way that mimics these ideas from the sacred texts. A way that supplements, rather than substitutes for, our physical existence. Ripatrazone affirms that in the electronic world, “We are more than our bodies. Online, we are all soul.”[26] Hardly a cold center of rationalism, the Internet, with its ever-growing collection of creative software, allows us to tap deeper into our souls when crafting messages to others than any other medium that came before it. “God and the imagination are one,” wrote Wallace Stevens,[27] and Ripatrazone leans on this line to justify the liturgical dimension of this phenomenon. Poetry, painting, and other manifestations of art have gotten us close to this moment. But those messages from the soul are always unidirectional.

The most important idea found throughout McLuhan’s media theories is that a good communications medium emphasizes the soul. The true appeal of digital technology lies not in its ability to make us more productive or entertained, but instead in its social dimension. A Christ-like medium goes even a step further: a digital communion that cultivates the common good across its users instead of indulging their individual impulses. If made to serve mankind’s God-given dignity, digital technology does not abolish the body, rather it can help order our strivings to fulfill our supernatural destiny.

Thus, McLuhan’s writings have prophetic value in a particularly Catholic sense. Within the Internet’s myriad connections, a new heaven and a new earth might just take shape while the former versions gently pass away.

For instance, try avoiding scrutiny while working on artificial intelligence these days. See Matteo Wong, “We Haven’t Seen the Worst of Fake News,” The Atlantic, 20 December 2022, online. ↩︎

See “IBM: early 1990s Commercial,” 3 October 2016, YouTube. ↩︎

Marshall McLuhan, The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man (Boston: Beacon Press, 1951), 50. ↩︎

The “Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link” (WELL) is widely acknowledged to be a bridge between the counterculture of the 1960s and the dotcom era of the 1990s. Brand cut his teeth as a Merry Prankster in the mid-1960s, but had pivoted to the technology industry by the 1980s, and remains influential in Silicon Valley today. ↩︎

Marshall McLuhan, “To Clement McNaspy, S.J.” (1946), Letters of Marshall McLuhan, eds. Matie Molinaro, Corinne McLuhan, and William Toye (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 180. He continues:

“My increasing awareness has been of the ease with which Catholics can penetrate and dominate secular concerns— thanks to an emotional and spiritual economy denied to the confused secular mind. But this cannot be done by any Catholic group, nor by Catholic individuals trained in the vocabularies and attitudes which make our education the feeble simulacrum of the world which it is. It is enough that it be known that the operator is a Christian. This job must be conducted on every front— every phase of the press, book-rackets, music, cinema, education, economics. Of course, points of reference must always be made. That is, the examples of real art and prudence must be seized, when available, as paradigms of future effort. … These can serve to educate a huge public, both Catholic and non-Catholic, to resist that swift obliteration of the person which is going on. … Dialectics and erudition are needed, but, without the sharp focusing of training in moral sensibility, futile.” ↩︎Marshall McLuhan, “The Electric Culture,” Renascence, vol. 13, no. 4 (Summer 1961), 220, online. ↩︎

Nick Ripatrazone, Digital Communion: Marshall McLuhan’s Spiritual Vision for a Virtual Age (Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press 2022), 81.

According to Ripatrazone, it is not explicitly utopian or dystopian. There is a duality in McLuhan’s thinking about the Global Village from the late 1950s through the 1970s. This makes some sense, as a village isn’t universally pleasant or unpleasant depending on what one is doing, who one is talking to, etc. It is a capsule of experience. Here McLuhan extends that to the entire planet. As it does not override distinct communities, the Global Village merely connects them together in a new way. That causes new friction among communities but does not negate them. ↩︎Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore, The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects (1967), produced by Jerome Agel.(Corte Madera, CA: Gingko Press, Inc.), 85, online. ↩︎

“...any text is constructed as a mosaic of quotations; any text is the absorption and transformation of another.”

Julia Kristeva, “Word, Dialogue, and Novel” (1966), The Kristeva Reader, ed. Toril Moi (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), 37. ↩︎Lawrence Laurent, “Canadian Scholar Stirs Controversy,” Washington Post, 5 April 1966, B4. ↩︎

In his cameo appearance in Woody Allen's film, Mcluhan says: “I heard what you were saying. You know nothing of my work. You mean my whole fallacy is wrong?” What does he mean by that? This line was one of McLuhan’s recurring meta-jokes. As he explained to Pierre Trudeau: “I have yet to find a situation in which there is not great help in the phrase: 'You think my fallacy is all wrong?' It is literally disarming, pulling the ground out from under every situation! It can be said with a certain amount of poignancy and mock deliberation.”

Quoted in Gary Wolf, “The Wisdom of Saint Marshall, the Holy Fool,” Wired, 1 January 1996, online. ↩︎Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (New York, 1964), reissued (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994), 57. McLuhan continues: “That is what is meant when we say that we daily know more and more about man. We mean that we can translate more and more of ourselves into other forms of expression that exceed ourselves. Man is a form of expression who is traditionally expected to repeat himself and to echo the praise of his Creator. "Prayer," said George Herbert, "is reversed thunder." Man has the power to reverberate the Divine thunder, by verbal translation.” ↩︎

Nick Ripatrazone, Digital Communion: Marshall McLuhan’s Spiritual Vision for a Virtual Age (Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press 2022), 58. ↩︎

T.S. Eliot, “Ulysses, Order, and Myth,” The Dial (November 1923), online, quoted in Marshall McLuhan (with Wilfred Watson), From Cliche to Archetype (New York: Viking Press, 1970), 139-141. ↩︎

“Much more easily than by printed books, these technical arts can assuredly provide opportunities for men to meet and unite in common effort; and, since this purpose is essentially connected with the advancement of the civilization of all peoples, the Catholic Church - which, by the charge committed to it, embraces the whole human race - desires to turn it to the extension and furthering of benefits worthy of the name.”

Pope Pius XII, Miranda Prorsus, 8 September 1957, online. ↩︎Even the Carthusians and Cistercians, the severest of Catholic religious orders, maintain a vigorous presence on the Internet. For one notable example, see here. ↩︎

Katelyn Beaty, “Geek Theologian,” Christianity Today, 15 July 2011, (online)[https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2011/julyweb-only/geektheologian.html]. ↩︎

“”[I] was very influenced by McLuhan. . . . We all thought, "This is one of the great prophets of our time." What's happened to him? Why are these people reading Lacan or Foucault who have no awareness at all of mass media? Why would anyone go on about the school of Saussure? In none of that French crap is there any reference to media. Our culture is a pop culture. Americans are the ones who have to be interpreting the pop culture reality.

Stewart Brand, interview with Camille Paglia, “Scream of Consciousness,” Wired, March/April 1993. ↩︎For the fascinating recent history of this approach to decentralization, see Kevin Driscoll, The Modem World: A Prehistory of Social Media (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2022). ↩︎

Though some debate exists as to whether a simple printing error led to the variation, much to McLuhan’s delight. ↩︎

Marshall McLuhan, “McLuhan: Now the Medium is the Massage,” New York Times, 19 March 1967, D23. ↩︎

Ripatrazone, Digital Communion, ibid, 102. ↩︎

Marshall McLuhan, “To Tony Schwartz” (30 August 1973) Letters, ibid, 480. ↩︎

Marshall McLuhan, The Medium and the Light: Reflections on Religion, eds. Eric McLuhan and Jacek Szklarek (New York: Stoddart Publishing Co., 1999), 103. ↩︎

Ripatrazone, Digital Communion, ibid, 128. ↩︎

“Within its vital boundary, in the mind.

We say God and the imagination are one...

How high that highest candle lights the dark.”

Wallace Stevens, “Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour” (1951), online. ↩︎

Walter J. Scheirer, having previously taught at Harvard University, is the Dennis O. Doughty Collegiate Professor of Engineering in the College of Engineering at the University of Notre Dame. There his team, among other things, uses artificial intelligence to study ancient manuscripts, and is developing a warning system to identify visual misinformation online. A holder of four patents and author of over 30 journal articles and book chapters, he is an Associate Editor-in-Chief for Pattern Recognition, an Associate Editor for IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, as well as the author of Extreme Value Theory-Based Methods for Visual Recognition (2017), and the co-author of Quantitative Intertextuality (2019). Also a contributor to Comment, Scheirer’s new book, A History of Fake Things on the Internet (Stanford University Press, 2023), has been named one of “The Best Books of 2023” by The New Yorker, and was featured both there and by The Washington Post. He invites you to follow him on X, or his personal website.

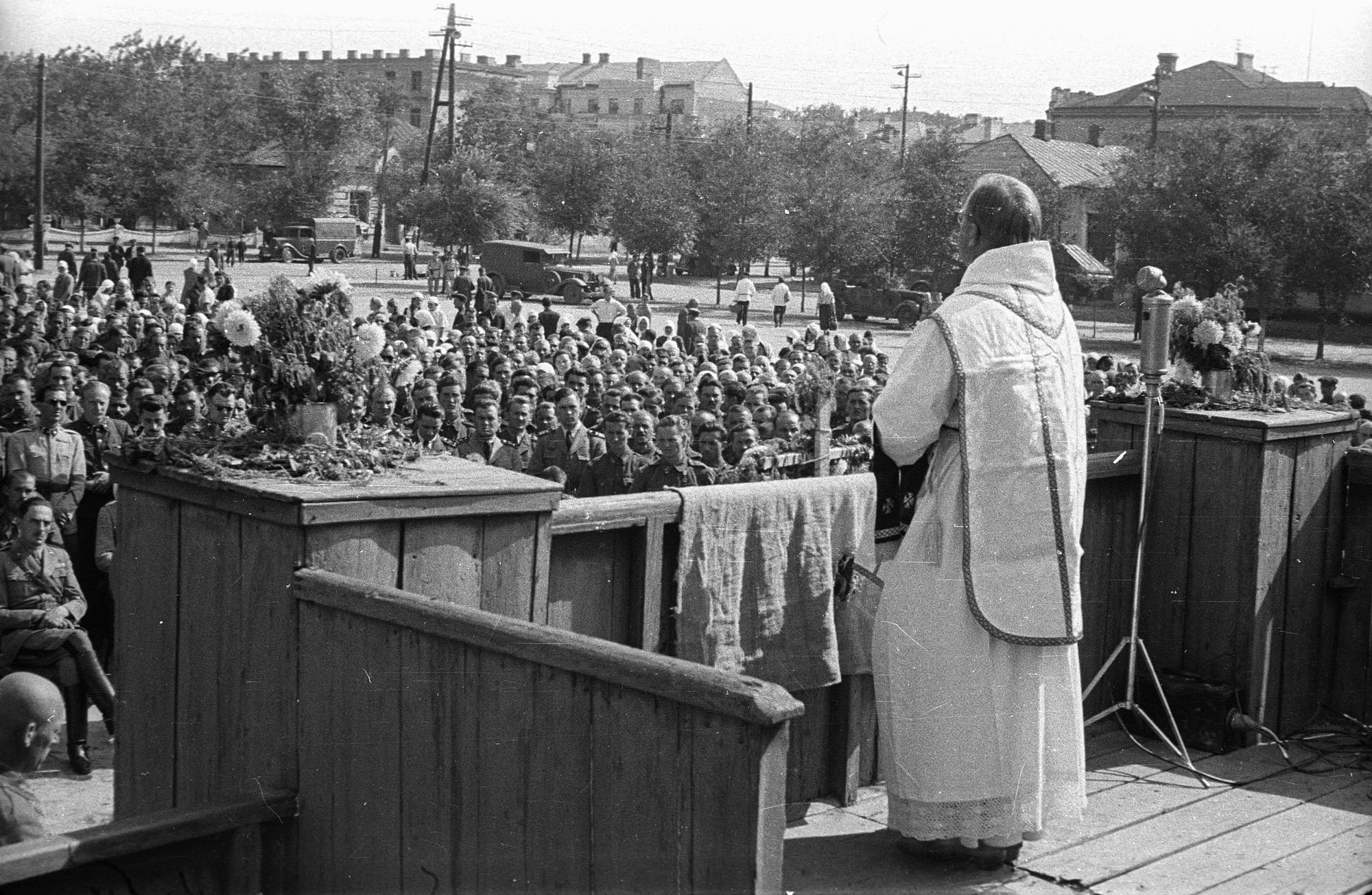

Featured image: Image of a priest celebrating mass in photo by Berkó Pál via Wikimedia Commons.