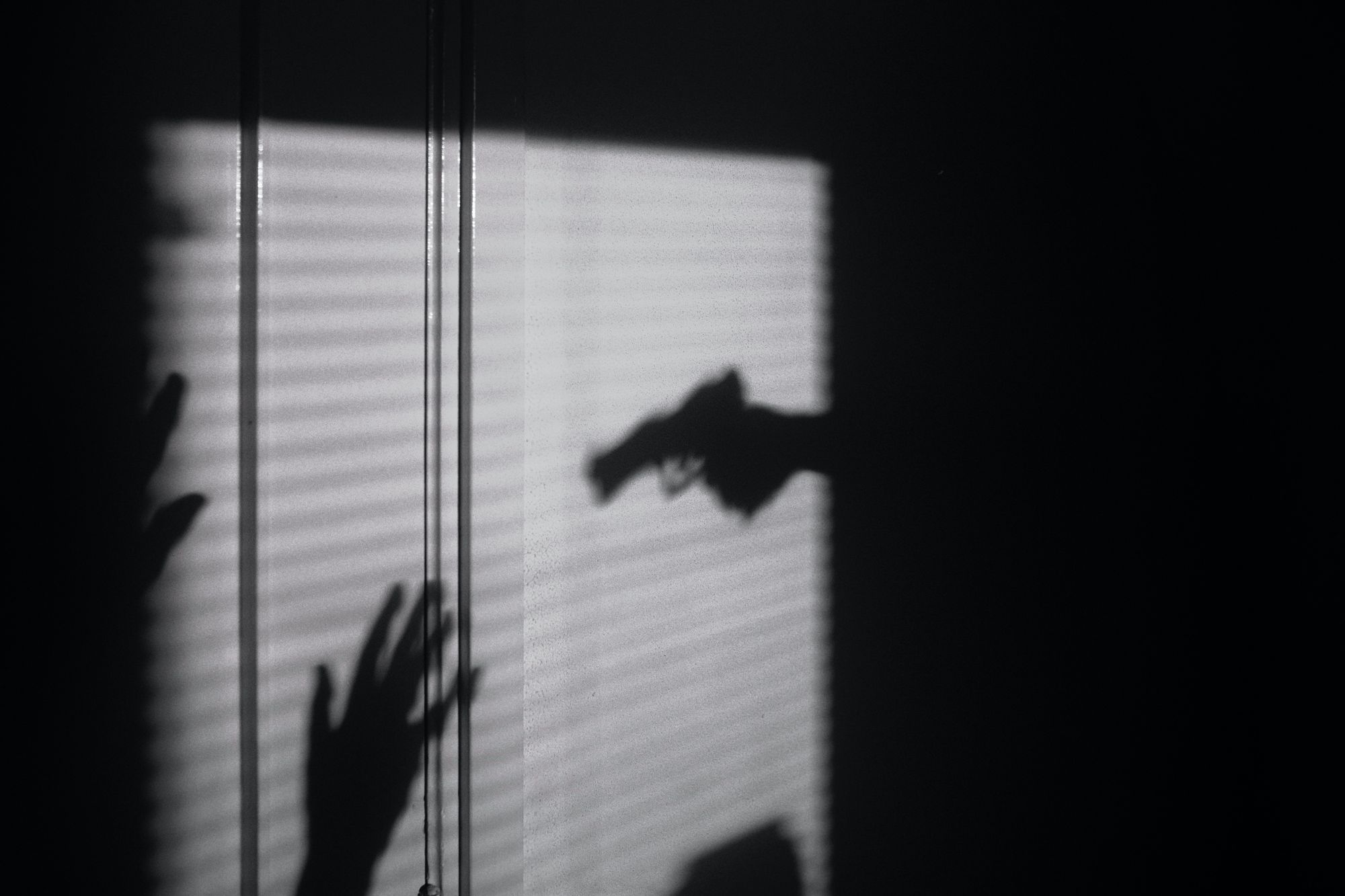

Criminality is an unlikely candidate for hyperreality. After all, it necessarily involves tangibility, some form of intentional and actual harm outside of pure cyberspace. Despite this, true crime, the documentary style window into murder and mayhem, has emerged as the latest in “indistinguishability,” occupying the hyperreal space between reality and simulation. The essences and implications of true crime and its most potent medium, the streaming service, are manifold. Part tragedy, part voyeurism, part hologram, and part séance, true crime renders us unable to distinguish between life and death. From culture industry to “murder machine,” streaming’s crown jewel of entertainment administers short-lived catharsis and collapses death, mourning, and eulogy all into flat, lurid infotainment.

Voyeurism and Catharsis

In his Poetics, Aristotle proposes several essential elements for tragedy. They are plot-driven, the misfortune occurs because of error rather than vice, and the character experiences a negative reversal of fortune, all the while depicted as better in the story than in real life. The complete work ultimately produces katharsis. Tragic catharsis is the quasi-medical purgation of fear and pity. This purgation of excessive fear and pity is both personal and social. By observing a character’s reversal of fortune, the spectator shares in this reversal and discharges their overflow of fear and pity. Such a reversal is best when it is the product of hamartia, or “to miss the mark,” understood in Greek tragedy as a mortal error in judgement.

Such tragic flaws are, as Malcom Heath explains, “errors made in ignorance or through misjudgement; but it will also include moral errors of a kind which do not imply wickedness.” It is essential that whatever horrors that afflict the protagonist are not “due to any moral defect or depravity, but to an error”—if these were deserved punishments, the spectator would not feel fear and pity, but rather the satisfaction of justice being done.

In Greek tragedy, there were limits on what could be staged. When Phrynichus showed his play The Fall of Miletus in 494 BC, which depicted the Persian sacking of the Athenian allied city, “the whole theater fell to weeping” and the unlucky tragedian was fined one thousand drachmas—the equivalent to two years wages for unskilled labor. Herodotus recounts that this play “[brought] to mind a calamity that affected them so personally, and forbade the performance of that play forever.” The city attempted to maintain balance between civics and poetry. What happened to Phrynichus helps illustrate a crucial distinction between Greek tragedy, which often recounted figures from myth and history who were thought to be real, and true crime, which recounts “true” events into myths to be binged. Unlike the Athenian audience, true crime voyeurs lack moderation, that some things should not be revived. Sometimes the dead should stay buried.

True crime satisfies all of these conditions, except one—there are no limits we might, like Athens upon Phrynichus, put upon the subject matter as depicted. The genre is stocked with plot-driven narratives where some horror, usually murder, afflicts an undeserving victim by virtue of hamartia (even something as simple as being in the wrong place at the wrong time), catalyzing a change to bad fortune (from life to death), as well as the sufferer being given a morally exemplary status. Finally, as the audience approaches catharsis, they are invited into recognition, the flash of memory or observation that ties a tragic narrative together. In true crime, this is the culprit’s ritual unveiling, which typically peels back the layers of his life in an attempt to understand the cause of his criminality. Despite the similarities, there are two key distinctions between Greek tragedy and true crime. First among them is that the events portrayed by true crime are necessarily real, involving actual events and persons. Second are their respective mediums—the former a product of theater, the latter of television, and more specifically, streaming services.

The result is a mixed experience, wherein the experiences of spectator and voyeur are blended. As the former, audiences passively absorb aestheticized reporting, an entertaining, depersonalized transmission of facts. As the latter, audiences enter the private lives of victims, perpetrators, and families, privy to information that is only obtained in “real life” through privacy violations. This thrill is, in effect, the secret and addictive ingredient which distinguishes true crime from other tragic modes. The spectator simultaneously experiences catharsis and thrill, the rush produced by a simulated overstepping of boundaries. This taboo tango lends true crime a “viewership rhythm” lacking on the stage or on the big screen—a cycle of thrill, catharsis, temporary separation, and inevitable return—via a simple click or even passive inaction as autoplay takes charge. If pure tragedy delivers fear and pity by proxy, true crime does the same for horrible exhilaration: the sensation of a telephone call waking you up in the night. True crime, in other words, is the logical conclusion of streaming services as an online medium. Content versus form, producer versus consumer, actor versus audience are no longer clear and distinct categories. With online true crime, the audience is assimilated into the performance.

Thus, true crime goes beyond tragic catharsis into hyperreality. Fear and pity are expunged for a time, but the endless stream of taboo thrills also rekindles desire in its voyeuristic viewers. So who are these viewers? It is common knowledge that audience viewership for true crime is predominantly female. While men wrote 82% of Amazon reviews for books on war, one study showed, women wrote 70% of Amazon reviews for books on true crime. In Savage Appetites (2019), a telling of four crime stories, Rachel Monroe recounts attending a CrimeCon where “the true crime obsessives packing the hallways” being “almost all women was, on its surface, perplexing.” Men commit the vast majority of violent crimes and are a majority of murder victims. Homicide detectives, criminal investigators, and criminal attorneys are all predominantly male. “Put simply, the world of violent crime is masculine, at least statistically,” Monroe writes, yet, from the majority of book readers to podcast listeners, “the consumers of crime stories are decidedly female.” From television executives to writers, forensic scientists, as well as activists and exonerees, Monroe writes, “all agree: true crime is a genre that overwhelmingly appeals to women.”

Notably, Monroe offers a peculiar reason to explain the predominantly female audience. The fandom goes beyond avid interest into joining in the performance and crafting the narrative: “Women aren’t just passively consuming these stories; they’re also participating in them.” The majority of posters in online sleuth forums, where amateurs speculate on and sometimes solve unsolved crimes, are female, as Monroe notes. Also, she mentions, women are driving the growing college major of forensic science while Cold Case Clubs at universities are, again, mostly female. On this female fandom, Monroe writes:

“True crime wasn’t something we women at CrimeCon were consuming begrudgingly, for our own good. We found pleasure in these bleak accounts of kidnappings and assaults and torture chambers, and you could tell by how often we fell back on the language of appetite, of bingeing, of obsession. A different, more alarming hypothesis was one I tended to prefer: perhaps we liked creepy stories because something creepy was in us.”

Whatever the merits of her explanation, it illustrates the effect true crime has on its consumers: they become participants. Each documentary miniseries takes the spectator deeper into hyperreality. Each completed cycle transports the spectator further into a place beyond life or death, a twilight zone called the internet whereby they, if not we, gradually lose all meaningful sense that the victim is, in fact, dead and buried.

Hyperreality and Hyperdeath

Hyperreality is a technical achievement of experiencing virtual life without its finitude. In Simulacra and Simulation (1981), Jean Baudrillard proposed that with television, society had irrevocably dissolved the barrier between reality and its simulation, to the point that simulacra, copies without originals, had begun to dominate human affairs and human consciousness. Baudrillard compares holograms, the televised phantasms that reach through television screens to audiences at home, to a “dead twin that is never born in our place, and watches over us by anticipation.” This effect remains in true crime but in reverse, whereby we summon a stranger’s ghost, project them into a future where they are dead, and activate them to relive their final moments in anticipation. This is hyperdeath.

American Murder: The Family Next Door, is particularly emblematic of this phenomenon. It documents the annihilation of Chris Watts’s family, primarily through the social media posts of his wife, Shanann Watts. Throughout the film, Shanann Watts is made to seem overbearing and overly online. There is so much Facebook footage of her and her daughters that the spectator routinely forgets they are dead, to cyclically remember and then forget this fact once more. Beyond these graphics, intimate text messages and private communications are put on full display, assembling a holographic golem from all this information that happens to bear the name Shanann Watts. For all intents and purposes, this golem is Shanann Watts as spectators have no other point of reference by which to differentiate the two. If Baudrillard is correct that “hypersimilitude was equivalent to the murder of the original, and thus to a pure non-meaning,” then Netflix’s golem effectively neutralizes the reality of Shanann Watts, obscuring her person from their projection. They are “united in a work of death that is never a work of mourning,” only a montage of events relentlessly advancing the plot forward to produce catharsis. This catharsis does come, but the murders are never truly resolved. Instead, they are summoned again and again by viewers across the globe, producing a remainder, an ectoplasm that is impossible to scrub out or erase. In this way, true crime points to Baudrillard’s thesis that “death is residual if it is not resolved in mourning, in the collective celebration of mourning.” True crime never gives way to such a celebration, only unending loops and streams.

The Medium is the Message

Documentaries are made up of “actuality film,” the raw and formless footage that is later threaded into a coherent narrative. In American Murder, the actual film used is mostly drawn from Shanann Watts's Facebook videos and text messages. In The Vanishing at Cecil Hotel, eerie security camera footage functions as the documentary’s anchor. Baudrillard’s description of the supermarket as a “giant montage factory” is more literally applicable to the streaming service, which strings actual footage together as life-montages of murderer and murdered alike. Ironically, this contemporary actuality film, primarily drawn from social media, is anything but real. It is itself a simulation of the real, a virtual replication of an authentic person. This mimicry is her “dead twin” who was never born—but whose anticipation is over.

Further, Adorno and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944) captures the montage factory’s essence and social effect. The culture industry, that amalgamation of pop cultural production today best represented by streaming services, has an “inherent tendency to adopt the tone of the factual report . . . [that] makes itself the irrefutable prophet of the existing order.” Under streaming’s augury, there is no such thing as culpability or interpretation. Rather, the onus is shuffled onto the consumer rather than the producer, with the sequence of events set down in televised stone. Their assertion that “products of the culture industry are such that they can be alertly consumed even in a state of distraction” has a double meaning for true crime: not only can we consume it in a stupor, but also the audience is subjected to an “enforced bystander effect,” a fixed position of passivity in the face of gruesomely detailed murders. The streaming services become both prophets and perpetrators, and, the authors continue, “make themselves into the vehicle of the moral condemnation of terrorism and of the exploitation of fear . . . but simultaneously, in the most complete ambiguity, they propagate the brutal charm of the terrorist act, they are themselves terrorists, insofar as they themselves march to the tune of seduction.” Substitute terrorist for murderer, and you reach the heart of streaming’s relationship to true, or real crime. Netflix and the others are morally and mortally invested in the production of new murders, ever stranger and more heinous, in real life and its digital resuscitation.

Scouts survey the earth for patches of blood, which might coagulate into celluloid fit for a miniseries or documentary special. Ever-greater sophistication in editing, narration, and general storytelling has converted notable murders into simulated murders, so much so that they are already inscribed in the decoding and orchestration rituals of the media, anticipated in their presentation and their possible consequences, as put by Adorno and Horkheimer. Before the crime itself is concluded, it is possible to know how it will be framed, vivisected, and rearranged for maximum thrill and catharsis. In this sense, the streaming service takes more ownership and authorship of a murder in its retelling than the murderer himself, who becomes just another cast member in a broader production.

In The Vanishing at Cecil Hotel, Netflix goes so far as to create a murderer where there is none. Over the course of the miniseries, bizarre synchronicities are laid out before viewers as evidence of foul play. Striking security camera footage of the “victim” Elisa Lam, similarities between her death and the film Dark Water, and the genuinely cursed history of the Cecil Hotel itself. Eventually, the truth comes out. Rather than “true” crime, Lam suffered from severe bipolar disorder and was likely spurred by hallucinations into suicide or accidental death. In the absence of a murderer, Netflix invests itself in creating a simulacrum of one: illustrating motivations, method, and personality, among other elements. Netflix produces a copy of that, without an original, and places it within a murder which does not exist. The documentary even shows a certain desperation of internet sleuths for connection with the deceased. Producers and viewers eventually share in this desperation. It is this fundamental need to commune with Lam that hints at true crime’s other nature beyond that of tragedy or thrill-machine. Even when there was no real crime, True Crime is stranger as fiction.

Streaming and Séance

Streaming services have resurrected an age-old practice: the séance. Séances were performed for many reasons. Some served as cathartic encounters with loved ones, others as marvels of ectoplasm and floating tables. There are examples in every age, from the earliest ancestor worship onward. In the First Book of Samuel, Saul initiates a forbidden rendezvous with the Witch of Endor. At Saul’s request, she summons Samuel’s spirit. Rather than counseling him on the upcoming battle against the Philistines, Samuel rebukes Saul and prophesies his imminent defeat and death. Now, Saul had previously banished all “mediums and spiritists from the land” (1 Sam 28:3), executing their Mosaic legal prohibition. He breaks his own rule and seeks help from a pagan because, he tells Samuel, “God has departed from me. He no longer answers me, either by prophets or by dreams” (28:15). When God was absent, spiritualism was the fallback option. Maybe it is the fallback for us as well, when left to our own devices, metaphorical and mechanical. In one passage, Deuteronomy lists prohibitions against all kinds of pagan practices: let none consult diviners or sorcerers, enchanters or witches, charmers or mediums, wizards or necromancers (18:10-12). Perhaps the Torah is so emphatic because these practices do not just distract from true worship of the divine, but are reflexive to fallen human nature. Maybe that is why these pagan practices have reeemerged in recent centuries. The Victorian era Spiritualists summoned figures from history and the ghosts of dearly departed. Mary Todd Lincoln famously held séances in the White House, attempting to reach her deceased son in the hereafter. Man’s desire to commune with the dead remains, but popular means for doing so have changed. Yet there remain disquieting parallels between the spiritualist mediums of ancient times and online mediums today.

If Saul were a Victorian, he would have used scientific advances to summon Samuel back from the dead. Modern occultism was, paradoxically, technological in its approach. When Marie and Pierre Curie held séances in their laboratory, they used science to rebel against its disenchanting effects. True crime consumers mimic such past voyeuristic audiences who watched the dead be summoned by mediums back to life in visual form, using digital technology to escape from its disenchantment. Here, spiritualism is the godfather to true crime. Both are pursuits attempting escapes from yet ultimately reaffirming the “technological society.” The occult critiqued “the limits of science,” Jason Josephson-Storm notes in The Myth of Disenchantment (2017), “by presenting the world paradoxically and vibrantly alive with the souls of the dead.” Spiritualists sought to escape scientism by procuring miracles to scientifically prove materialism incomplete. Consumers seek to escape pacified domestic life by using technology to relive the thrills and chills when that ennui gets interrupted by evil. This escape is always botched: the digital technology only pacifies and domesticates its viewers. So, true crime consumers imitate not only their forebears of occultist audiences communing with the depart. Viewers also mimic the digitally resurrected dead, since both spectator and actor, consumer and producer are all rendered docile and manipulable through their mutual participation in this digital necromancy. Notably, spiritualists intended, as Josephson-Storm notes, the séance to be “a religious laboratory” that could by an empirical route modernize religion. These “occult sciences” rebelled against Enlightenment thinking while they benefited from its assumptions. Instead, science and religion would be fused together: “empires of reason” would become a “science of spirits.” True crime, a digital godchild of spiritualism, is also its dead twin whose anticipation is now fulfilled with online spiritualism.

In late modern society, séances are making a comeback, in literal and figurative forms.

It was assumed roadside palm-readers had been reduced to drooping shacks and shotgun houses. Even mediums experienced a temporary revival through reality television, and one might think they have since been supplanted by true crime. Yet, in its literal form, new age and occultists ideas are making a comeback, as Tara Isabell Burton notes in Strange Rites (2020), thanks to the group sorting and information gathering of digital technology, from the social justice left to the atavistic right, with technocratic futurists in the middle. Spirits are no longer summoned through spell and incantation as done by Saul as well as Mary Todd Lincoln, but through streaming and simulation. In this new remixing of religion, be it “fan fiction, or memes, or other aspects of our digital footprint,” as Burton writes, “we learn to expect stories to be made in our image.” It was for this reason, the idolatrous worship of oneself, that Mosaic law punished the magic of mediums. Only God could raise the dead. But our digital imitation is godlike. On a whim, we can relive the final moments of a victim’s life, or bask in recordings of their better days. True crime, in this way, renders us unable to distinguish between life and death.

Cinematic Spiritualism

The internet does not respect, but comingles, the poetic distinctions that Aristotle described. There was thought to be the thing in nature and its depiction in art. In facing actual tragedy, we should suffer the appropriate passions. In watching dramatic tragedy, we should experience such passions, not as actors in a scene, but as onlookers who feel emotions to let them go. If there was once the actors who mimic real deeds and spectators who mimic real feelings, our digital mediums ignore such Aristotelian niceties. Voyeurism for obsessives is on constant replay. This modern simulacrum of digital technology remixes not just actor and spectator, but depiction and catharsis, as well as the quick and the dead. In what Alexei Sargeant calls “the undeath of cinema,” Hollywood studios digitally reanimate dead actors for movies meant to be replayed endlessly upon streaming platforms: Peter Cushing will never rest as Grand Moff Tarkin. Rather, we the audience, deadened to any sense of finality, refuse the demands of finitude. And if we cannot distinguish between living and dead actors, in this condition, it is not so surprising that we ritualistically anticipate heinous crimes, so that we can experience the dead as if they were living. It is this modern necromancy that fully and finally blurs the lines between life and death. Baudrillardian “hyperdeath,” catharsis, and ghostland voyeurism all get unified in the séance always streaming on our screens.

We fit the description of another crime solver, one who too was plagued by an overload of crime. In The Man Who Knew Too Much (1922), G.K. Chesterton shows protagonist Horne Fischer as a detective who, because of his family relations to all important British government officials, knows too much of party politics to further anything real. Intimate with evil deeds, he is rendered a spectator by circumstance: he can investigate, but rarely for prosecution. Yet, in knowing his limits, he learns the proper distinctions of life. When he is investigating two murders and a vanishing suspect in Ireland, a few locals think the vanishing man is a ghost. His English colleague remarks that the Irish Catholics drink so much that of course they would believe in ghosts. But unlike the séances “you can get in your favorite London,” Fischer replies, “the Irish believe too much in spirits to believe in Spiritualism.” Such distinctions, between criminality and hyperreality, religion and necromancy, katharsis and its simulation, still exist. The verdict is in, and the spirits, like Samuel, want out, out of true crime and all of its criminal intent.

Works Cited

Aristotle. Poetics. Translated by Malcolm Heath, Penguin Books, 1996.

Burton, Tara Isabell. Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World. PublicAffairs, 2020.

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. 1981.

Chesterton, G.K. The Man Who Knew Too Much. Harpers and Brothers, 1922.

Crime Scene: The Vanishing at Cecil Hotel. Created by Joe Berlinger, Netflix.

Herodotus. Histories. Translated by A.D. Godley, Harvard University Press, 1920.

Heath, Malcolm. “Introduction.” Poetics. 1996.

Horkheimer, Max, and Theodor W. Adorno. “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception.” Dialectic of Enlightenment, 1947, pp. 94-136.

Josephson-Storm, Jason A. The Myth of Disenchantment. University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Monroe, Rachel. Savage Appetites. Simon & Schuster, 2019.

Sargeant, Alexi. “The Undeath of Cinema.” The New Atlantis. No. 53 (Summer/Fall 2017), pp. 17-32.

Yates, Diana. “Women, more than men, choose crime over other violent nonfiction,” University of Illinois News Bureau, 15 February 2010, https://news.illinois.edu/view/6367/205718.

American Murder: The Family Next Door. Directed by Jenny Popplewell, Netflix.

Featured image: Photo by Maxim Hopman via Unsplash.

Benjamin Roberts is an NYU Abu Dhabi undergraduate interning for the Wallace Institute. He has written previously for The Daily Caller, the Oxford Political Review, and others. He invites you to follow him on Twitter.

Ryan Shinkel is an Associate Editor. He is an alumnus of the St. John's College Graduate Institute. He invites you to follow him on Twitter.